This blog post is a shorter version of a paper presented at the Engaging with Web Archives (EWA20) conference in September 2020 (Book of Abstracts).

Budka, P. (2020). MyKnet.org: Traces of digital decoloniality in an indigenous web-based environment. Paper at Engaging with Web Archives (EWA20): “Opportunities, Challenges and Potentialities”, Online (hosted by Maynooth University), 21-22 September.

This blog post builds on selected results of an anthropological project that explored various indigenous engagements with digital media, technologies and infrastructures in Northwestern Ontario, Canada (e.g., Budka, 2015, 2019; Budka et al. 2009). The project was conducted in cooperation with the First Nations internet organization Keewaytinook Okimakanak Kuh-ke-nah Network (KO-KNET).

In this post I briefly reflect upon traces of “digital decoloniality”, a concept borrowed from Alexandra Deem (2019), by exploring selected aspects of the sociotechnical history of KO-KNET’s web-based environment MyKnet.org and by discussing facets of a MyKnet.org user’s digital biography.

KO-KNET & MyKnet.org

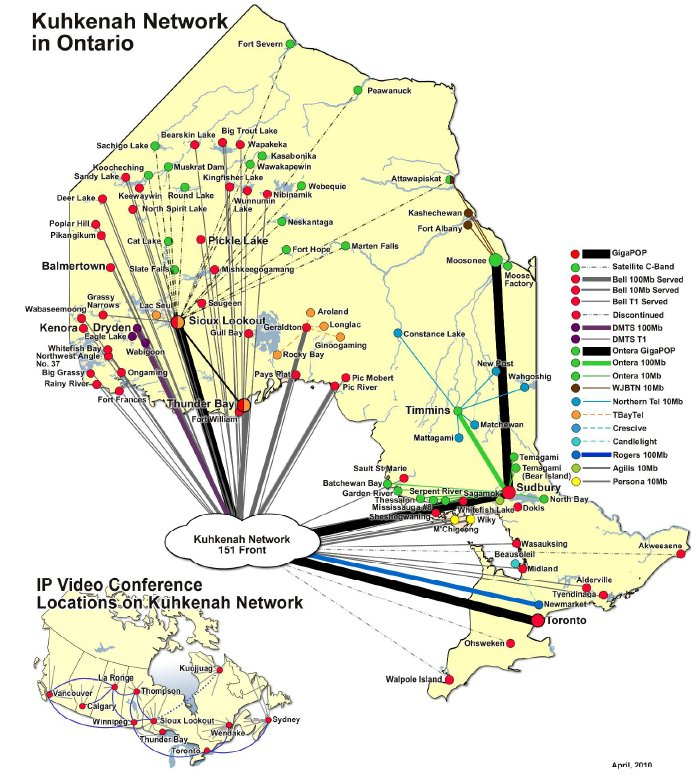

In 1994, the tribal council Keewaytinook Okimakanak (KO) established the Kuh-ke-nah Network (KO-KNET) to connect Canada’s indigenous people in Northwestern Ontario’s remote communities through and to the internet. At that time, a local telecommunication infrastructure was almost non-existent. KO-KNET started with a simple bulletin board system that developed into a community-controlled ICT infrastructure, which today includes landline and satellite broadband internet as well as internet-based mobile phone communication (e.g. Fiser & Clement, 2012).

Together with local, regional and national partners, KO-KNET developed different services: from e-health and an internet high school to different remote training programs. The most mundane of those services was the digital environment MyKnet.org, which enabled First Nations people to create personal homepages within a cost- and commercial-free space on the web.

MyKnet.org was set up in 1998 exclusively for the First Nations people of Northwestern Ontario. By the early 2000s, a wide set of actors across Northwestern Ontario, a region with an overall indigenous population of about 45,000, had found a new home on this web-based platform. During its heyday, MyKnet.org had more than 30,000 registered user accounts and about 25,000 active homepages.

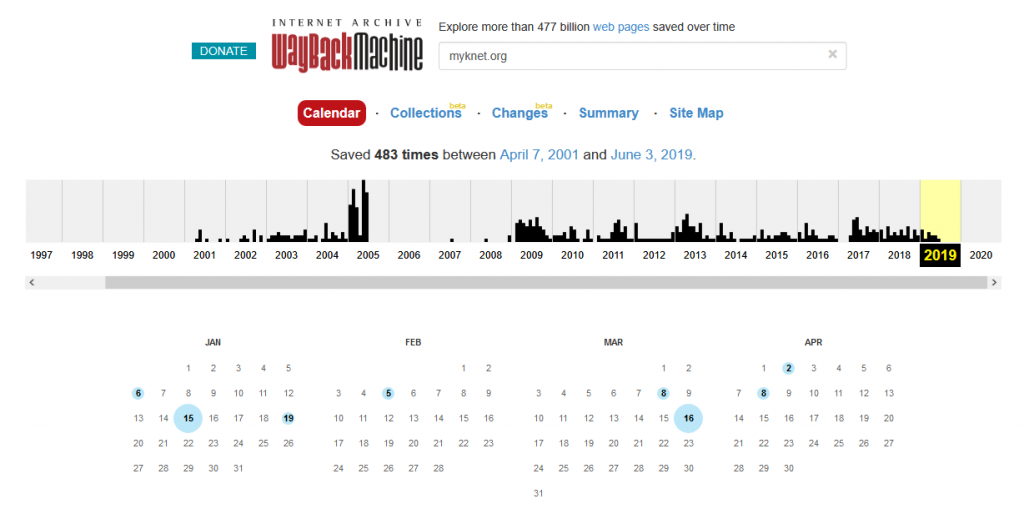

With the advent and rise of commercial social media platforms, such as Facebook, user numbers began to drop. To reduce administrative and technical costs, KO-KNET decided to switch to WordPress as hosting platform in 2014. Since this required users to set up new websites, numbers continued to fall. In early 2019, there were only 2,900 homepages left and MyKnet.org was shut down a couple of months later.

Particularly between 2004 and 2008, MyKnet.org used to be extremely popular among First Nations people. This was mainly because of two reasons.

- First, people utilized MyKnet.org to establish and maintain social relationships across spatial distance in an infrastructurally disadvantaged region. They regularly visited the homepages of friends and family members, which could easily be found because of MyKnet.org’s real name policy, to see what they were up to; they communicated via message boxes, and they linked their homepages to the pages of family members and friends. Creating thus a “digital directory” of indigenous people in Northwestern Ontario.

- Second, MyKnet.org contributed to different forms of cultural representation and identity construction. Homepage producers used the platform to represent themselves, their families and their communities by displaying and sharing pictures, music, texts, website layouts and artwork. Creating thus a great diversity of “digital selves” that also reflected their everyday life as indigenous people in a remote region.

Such practices not only required people to learn digital skills, they also contributed to the creation of an indigenous “territory” on the web (Budka, 2019) and thus to, what could be called, “digital decoloniality”.

Theoretical Reflections

The notion of “digital decoloniality” (Deem, 2019) is quite similar to what I have come to call “digital de-marginalization” (Budka, 2015) in my research on indigenous engagements with digital media technologies.

In the context of such engagements, both concepts direct us to “the localizing” (Postill, 2011) or – in the indigenous case – “the indigenizing” of digital technologies (e.g., Budka, 2019; Thorner, 2010). However, while Deem (2019) exemplifies her idea of digital decoloniality by referring to a Native American protest movement that has been aiming to avert the construction of a pipeline, by campaigning for example via Twitter, I am aiming to use this concept to frame rather mundane practices, such as sharing pictures and homepage layouts, in an indigenous web-based environment.

So is every indigenous activity online a form of mediated sociopolitical or cultural activism because of indigenous people’s history of structural oppression and violent experience? I don’t think so.

I argue, however, that little, routine practices in a digital environment that was created and controlled by an indigenous internet organization exclusively for First Nations people can contribute to larger processes of social and sociotechnical change that in the indigenous case can be described as processes of digital decoloniality.

Central to notions of digital decoloniality and digital de-marginalization as well as to ideas of internet localization and indigenization is change and, at the same time, continuity. By recognizing the inherent socio-cultural character of “the digital”, “digitality” and “digitalization”, moments of social, cultural and sociotechnical change become highly relevant. Not only change of digital media, technologies and infrastructures, but also of social interaction and cultural representation, for instance, that all together shape “the web” and “the internet”.

This requires us, as, for instance, Ralph Schroeder and Niels Brügger (2017) emphasize, to look into the everyday use of the web. And this is exactly what anthropologists and ethnographers of the digital have been doing (e.g., Hjorth et al., 2017): Critically exploring digital practices in a diversity of sociocultural, geographical and historical contexts by engaging with people, and their digital products and artefacts, an a day-to-day basis over a considerable period of time.

Such practices are, of course, changing; over time and space. The MyKnet.org websites of the early 2000s needed different handling and skills than Facebook profile pages do today. And Facebook pages and their content are maintained in surprisingly different ways in different countries and cultural contexts (e.g., Miller et al., 2016).

It is important here to distinguish between “social changing”, that is continuously happening, and “actual social change”, as John Postill (2017) puts it. Concrete moments of sociotechnical change that, for example, transform the way people communicate and interact, such as the introduction of broadband internet connectivity in remote First Nation communities. Equally important is to acknowledge that within such quickly changing environments, some digital practices point to the continuing of culturally specific ways of communicating or of establishing and keeping social ties.

In the case of my own research: How did MyKnet.org and the underlying sociotechnical infrastructure change? Why and how did people apply concrete changes to their personal websites? Which website functionalities and features were modified and replaced, and which were continued to be used? How did the remodelling of technical possibilities change digital practices?

Digital Ethnography & The Wayback Machine

In order to answer such questions, I not only observed and interviewed people, I also used the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine to recover archived versions of MyKnet.org websites whenever possible. Through this tool, I was able to explore older versions of personal websites. Adding thus another analytical dimension to my research.

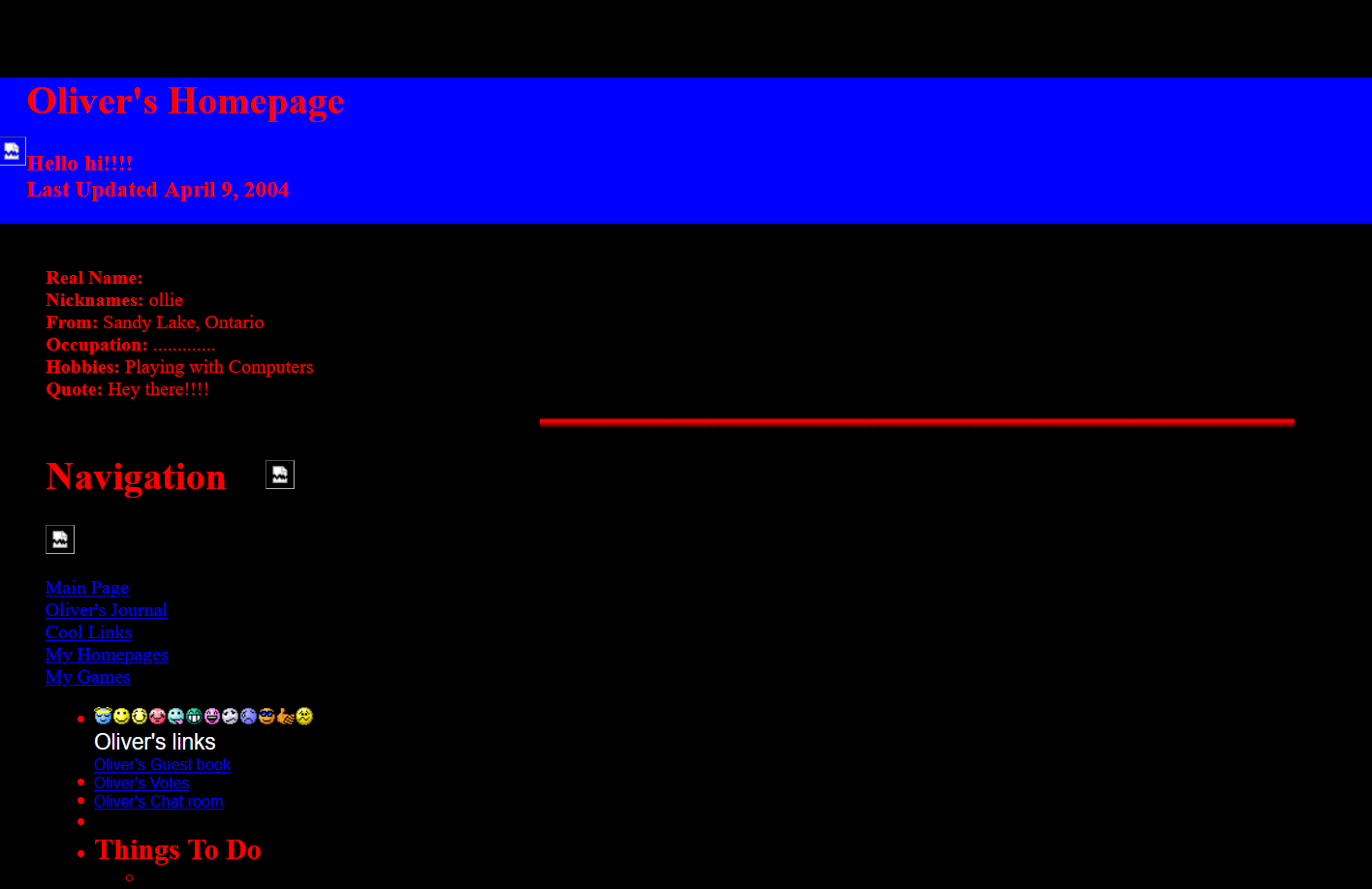

In the summer of 2007, I was interviewing Oliver, a 16 year old teenager from Sandy Lake First Nation, whose website was top-ranked in MyKnet.org’s official “most popular list” for years. Already when he was 12 years old, he was helping others to create websites and supposedly also managed to make use of his neighbour’s wireless internet, who happened to be the principal of the local school, because he had not enough bandwidth for his activities. People at KO-KNET told me that I should try to speak with Oliver because he used to be one of the most active MyKnet.org users, creating and sharing HTML music codes as well as website templates and layouts.

Digital practices that increased the traffic to his page, the numbers of visitors and hits, which were counted by almost all MyKnet.org users, and hence his reputation in this social field – or his social capital to speak with Bourdieu.

It was an unusually hot evening and we were sitting at a table in the house of my local host in the First Nations community of Sandy Lake. Right from the beginning of our conversation, I had the feeling that he was not really happy with being asked about his MyKnet.org experience. So after some questions and rather brief answers, we called it a day and I hoped for another opportunity to talk with him.

Six months later, I returned to Sandy Lake, desperately trying to get hold of him, but he didn’t answer my e-mails and also other attempts to contact him failed.

Because Oliver was such an important actor in and for MyKnet.org, I decided to use the Wayback Machine to look into his older pages for a comparative analysis. Thus trying to deepen my limited understanding of his digital practices and the changes in his digital biography. The oldest page I found was from April 2004, three years before our only conversation and one year after he started to create his first MyKnet.org website.

This page was built with a template provided by KO-KNET, like almost all of the early websites in MyKnet.org. It contained the usual elements, from title and update information to short personal information about the website owner and a collection of links to other websites, also on other servers. Moreover, Oliver’s page included above-average possibilities to contact and interact with him, such as a guest book and forms for sending messages. He also used many emoticons, particularly as design elements to structure the page.

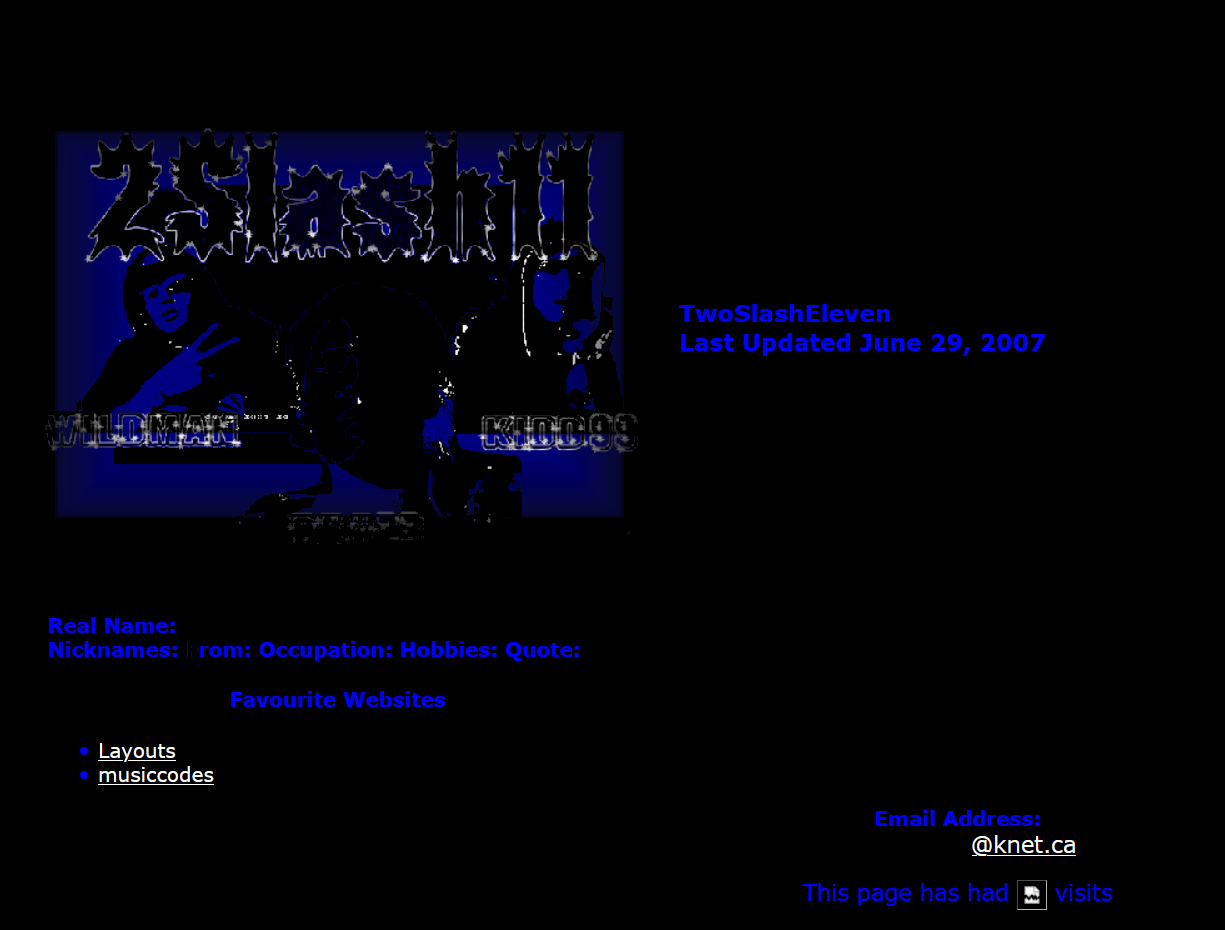

Comparing this page with the page Oliver was running in the summer of 2007, several differences can be identified. The page is structured and designed more clearly. A collage that suggests hip hop related images and gestures replaced the textual title. The collection of links referred mainly to his other MyKnet.org websites, where visitors could download music codes and layout templates from his huge collection. Also the possibilities to interact had changed: only an e-mail address allowed to get in touch. It seemed that Oliver had found his place within the MyKnet.org community. As producer, provider and archivist of digital artefacts, his page became one of the most visited and most popular ones.

Since summer 2012, his MyKnet.org pages were not updated any more and he stopped sharing website layouts and music codes. It seems that he had moved on to other digital platforms.

Conclusion

By building on the case of on indigenous web-based environment, I tried to show that web archives and tools, such as the Wayback Machine, can be used as an additional methodological instrument for digital ethnographic research. However, in an anthropological and ethnographic context, data collected via archival tools very much rely on a constant dialogue with data from participant observation or interviewing. Thus contributing to a diachronic dimension that is crucial for a deeper understanding of human engagements with digital media technologies.

This becomes not only relevant in attempts to (re)investigate digital environments that no longer exist, but also in the analysis of missing web or internet histories (Driscoll & Paloque-Berges, 2017), such as the history of MyKnet.org. A history that consists of many individual histories and digital biographies that are closely tied to changing and continuing digital practices and processes of decoloniality.

References

Budka, P. (2019). Indigenous media technologies in “the digital age”: Cultural articulation, digital practices, and sociopolitical concepts. In S. S. Yu & M. D. Matsaganis (Eds.), Ethnic media in the digital age (pp. 162–172). New York: Routledge.

Budka, P. (2015). From marginalization to self-determined participation: Indigenous digital infrastructures and technology appropriation in Northwestern Ontario’s remote communities. Journal des Anthropologues, 142-143(3), 127–153. https://doi.org/10.4000/jda.6243

Budka, P., Bell, B., & Fiser, A. (2009). MyKnet.org: How Northern Ontario’s First Nation communities made themselves at home on the World Wide Web. The Journal of Community Informatics, 5(2). http://ci-journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/568

Deem, A. (2019). Mediated intersections of environmental and decolonial politics in the No Dakota Access Pipeline movement. Theory, Culture & Society, 36(5), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276418807002

Driscoll, K., & Paloque-Berges, C. (2017). Searching for missing „net histories“. Internet Histories, 1(1–2), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701475.2017.1307541

Fiser, A., & Clement, A. (2012). A historical account of the Kuh-Ke-Nah Network. In A. Clement, M. Gurstein, G. Longford, M. Moll, & L. R. Shade (Eds.), Connecting Canadians: Investigations in community informatics (pp. 255–282). Edmonton: Athabasca University Press. https://www.aupress.ca/app/uploads/120193_99Z_Clement_et_al_2012-Connecting_Canadians.pdf

Hjorth, L, Horst, H., Galloway, A., & Bell, G. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge companion to digital ethnography. New York: Routledge.

Miller, D., Costa, E., Haynes, N., McDonald, T., Nicolescu, R., Sinanan, J., Spyer, J., Venkatraman, S., & Wang, X. (2016). How the world changed social media. London: UCL Press. https://www.uclpress.co.uk/products/83038

Postill, J. (2017). The diachronic ethnography of media: From social changing to actual social changes. Moment. Journal of Cultural Studies, 4(1), 19–43. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/451160

Postill, J. (2011). Localizing the internet: An anthropological account. New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Schroeder, R., & Brügger, N. (Eds.). (2017). The web as history: Using web archives to understand the past and the present. London: UCL Press. https://www.uclpress.co.uk/products/84067

Thorner, S. (2010). Imagining an indigital interface: Ara Irititja indigenizes the technologies of knowledge management. Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals, 6(3), 125–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/155019061000600303