Budka, P. 2014. Indigenous futures and digital infrastructures: How First Nation communities connect themselves in Northwestern Ontario. Paper at “13th Biennial Conference of the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA)”, Tallinn, Estonia: Tallinn University, 31 July – 3 August.

Introduction

“Now […] if the Aboriginal People could […], retain their tradition, take the technology and go that way in the future. That would be good.”

(Community Development Coordinator and Educational Director, Bearskin Lake First Nation, 2007)

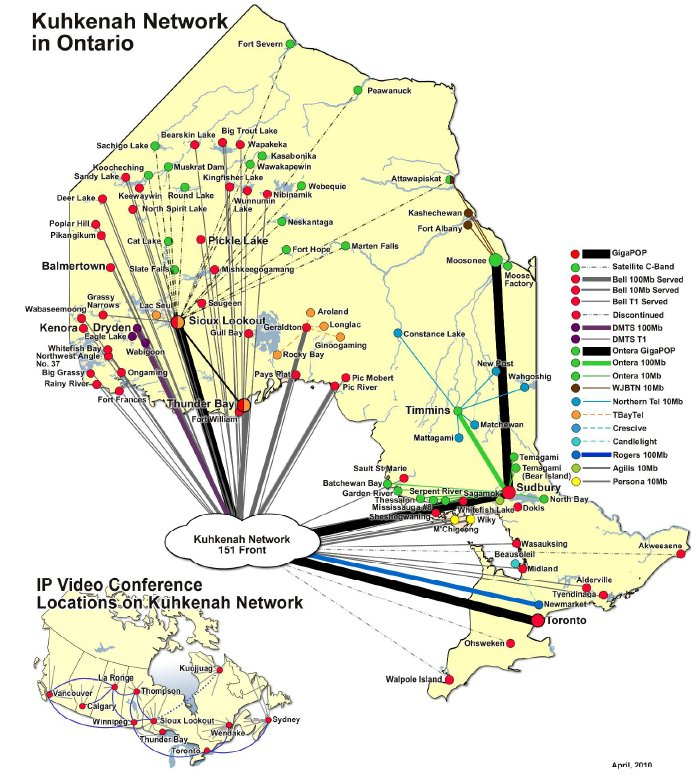

For my first field trip to Northwestern Ontario in 2006, I decided to take the train from Toronto to Sioux Lookout instead of flying. This ride with “the Canadian”, which connects Toronto and Vancouver, took me about 26 hours and demonstrated very vividly the vastness of Ontario. At some point, I could not believe that I have been spending more than an entire day on a train without even leaving the province. But finally I arrived at Sioux Lookout, Northwestern Ontario’s transportation hub, where I would be working with the Keewaytinook Okimakanak Kuhkenah Network (KO-KNET), one of the world’s leading indigenous internet organization.

After my first day at the office, KO-KNET’s coordinator told me that he wants to show me something. So we jumped in his car and drove to the outskirts of the town where he stopped in front of a big satellite dish. Only through this dish, he explained, the remote First Nation communities in the North can be connected to the internet. I was pretty impressed, but had no concrete idea how this really works. So while the satellite dish was physically visible to me, the underlying infrastructure was not. During my stay, I learned more about the technical aspects of internet networks and connectivity, about hubs, switches and cables, and about towers and loops. And I learned that internet via satellite might look impressive, but is actually the last resort and the most expensive way to establish internet connectivity. I also began to realize how important organizational partnerships and collaborative projects are and what important role social relationships across institutional boundaries play. In short: I learned about the infrastructure which is actually necessary to finance, provide and maintain internet access and use. Infrastructure, KO-KNET’s coordinator told me “really defines what you can do and what you can’t do” (KO-KNET coordinator 2007). And this has fundamental consequences for the futures of the region’s indigenous people.

Within this paper I am going to discuss digital infrastructures and technologies in the geographical and sociocultural contexts of indigenous Northwestern Ontario. By introducing the case of KO-KNET I analyse (1) how internet infrastructures act as facilitators of social relationships and (2) how First Nations people actively make their (digital) futures by taking control over the creation, distribution and uses of information and communication technologies (ICT), such as broadband internet. This study is part of a digital media anthropology project that was conducted for five years, including ethnographic fieldwork in Northwestern Ontario and in online environments.

In media and visual anthropology, anthropologists are, among other things of course, interested in how indigenous, disfranchised and marginalized people have started to talk back to structures of power that neglect their political, cultural and economic needs and interests by producing and distributing their own media technologies (e.g., Ginsburg 1991, 2002b, Michaels 1994, Prins 2002, Turner 1992, 2002). To “underscore the sense of both political agency and cultural intervention that people bring to these efforts”, Faye Ginsburg (2002a: 8, 1997) refers to these media practices as “cultural activism”. “Indigenized” media technologies are providing indigenous people with possibilities to make their voices heard, to network and connect, to distribute information, to revitalize culture and language, and to become politically engaged and active (Ginsburg 2002a, 2002b). Particularly digital media technologies offer a lot of these possibilities to marginalized people (e.g., Landzelius 2006a).

Text (PDF)